Bindings and Betweens: South Carolina Quilts

This online exhibition traces the history and art of South Carolina made quilts. Featuring pieces from the museum’s collection, the exhibition highlights both the objects and their makers for an in-depth look at the quilt making process and how it relates to cultural traditions throughout South Carolina history to the modern day.

Introduction

In these quilts we can explore the stories that bind people together and fill the spaces between us. Quilts tell us about globalization, cultural change, and technological innovations; topics we are all familiar with today. Quilts are also great ways to explore the lives of their makers. Who really made the quilt? Why did they make it? Where did they learn to quilt? Where did they get the fabric? What might have influenced their style choices?

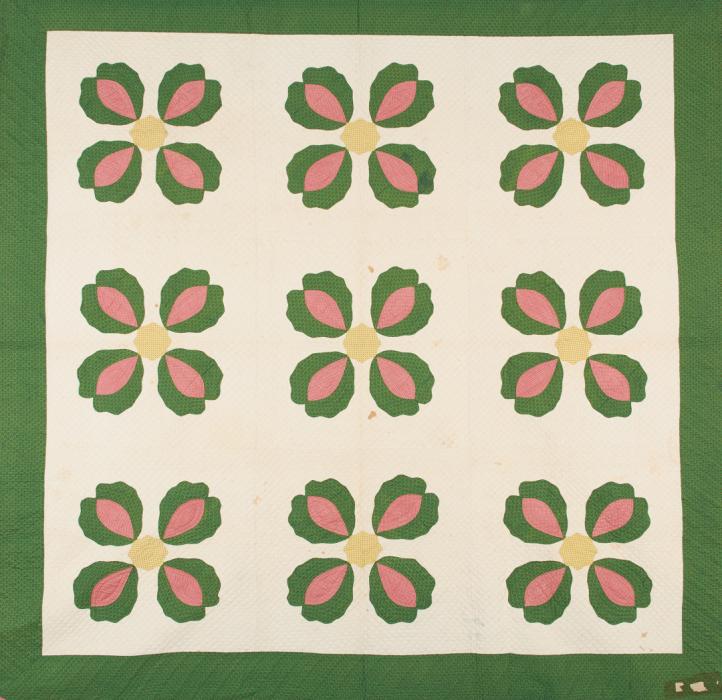

SC79.70.1. Unknown Makers, 1875. Anderson County. Donated by Mrs. William Kenneth Stringer.

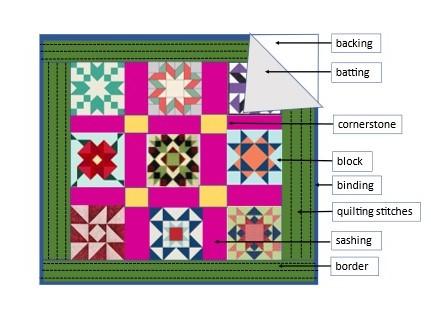

What is a Quilt?

Think of it as a fabric sandwich. Quilts have a fabric top, a soft middle called batting which is usually made of cotton, and a fabric backing. All three layers are stitched, or quilted, together. This is usually done with a special needle called a between. Quilts are also finished around the edges with a binding fabric.

How long has quilting been around?

Quilting has been around for thousands of years. Mostly, it was done on clothing for warmth or protection. In a time when most people only had one change of clothes, few had the means to buy the fabric needed to make quilts. Most people used blankets and coverlets. Quilting did not really become popular until textile innovations and growing trade networks made fabric more affordable in the late 1700s.

SC79.70.1. Unknown Makers, 1875. Anderson County. Donated by Mrs. William Kenneth Stringer.

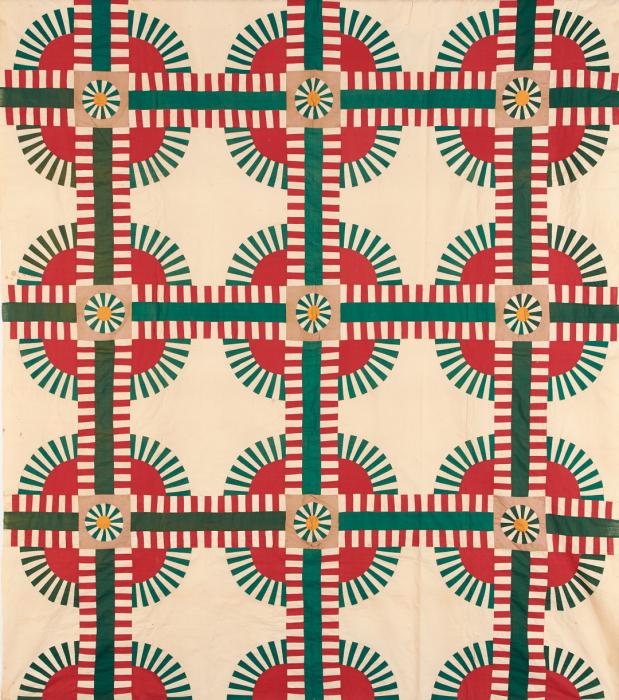

SC90.50.2

Carrie G. Coachman (1931-1999), 1947

Georgetown County

Museum Purchase

This is the bridal quilt of Carrie Coachman who married in 1947. In 1989, she was presented with a SC Folk Heritage Award in recognition of her quilting and community work. Her quilts often combined West African textile traditions and block designs of Euro-American quilting.

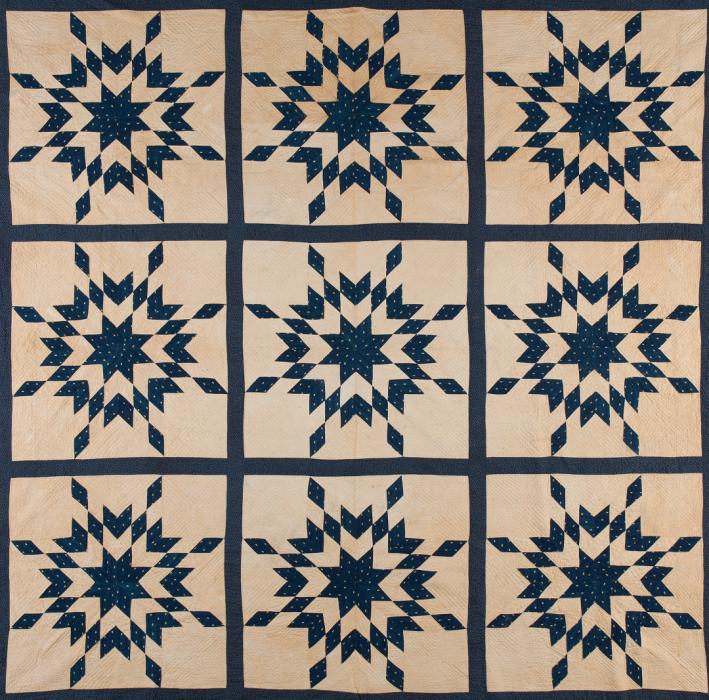

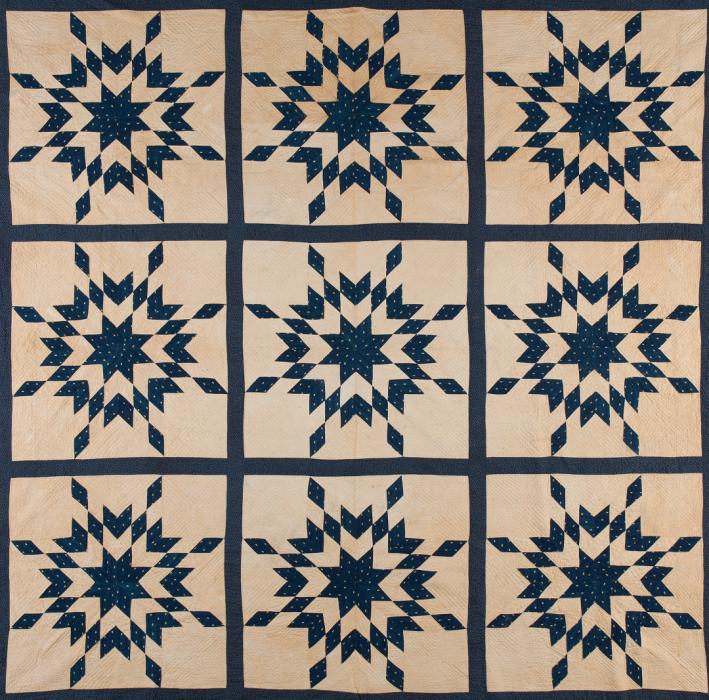

SC79.70.1

Unknown Makers, 1875

Anderson County

Donated by Mrs. William Kenneth Stringer

Quilts are often both make-do and showcases of creativity, skill, and beauty. While the top of this quilt shows off the virtuosity of its makers through the quilting, and use of color and fabrics, it also has a utilitarian backing of tobacco cloth.

SC84.62.1

Unknown and Rosa Lee Ott Strawhorn (1888-1968), 1856, quilted in 1940

Abbeville, Newberry, Columbia

Donated by the John G. Strawhorn Family

Album or Friendship quilts, like this, are comprised of blocks made by several people and then joined together into one quilt. The women who made these squares in 1856 did not complete the quilt. RosaLee Strawhorn found the quilt top in the trash in 1940. She added batting and a backing, then quilted it. She presented it to her son on his wedding day later that year.

The Power of Place

Quilt historians look for patterns, styles, fabrics, and techniques that seem specific to times and places. Quilts of the mid-1800s can look very different from quilts of the mid-1900s. Quilts made on the coast, look different, generally, than those in the upcountry.

The Fall Line

Quilts in this section were made from the 1850s-1890s in communities above the Fall Line. That is a geological boundary between the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain. Boats cannot navigate beyond that point because of rapids and falls. This significantly affects trade. This area was also settled differently than the coast. Many who settled there were Scotch Irish and German immigrants who travelled down the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia.

The combination of limited fabric choices, quilting techniques of the British Isles, and German decorative art traditions seems to have influenced these designs. They were passed around the community and down through generations. Not all quilts follow the “rules,” but when we learn what is similar and what is significantly different between these quilts, we can better understand how people are connected and it helps the individuality and creativity of the maker come through.

SC79.42.1

Unknown Maker from the Bray family, 1897

Richland County

Donated by C.H. Bray, Sr.

You can see the remnants of an entry tag for the 1897 S.C. State Fair on the right, bottom corner of this quilt. It reads: "Water-Melon quilt / Laid Werk." Laid work refers to applique, which is placing a piece of fabric on top of another and stitching it into place. This watermelon pattern is unusual and might reflect a regional style. Perhaps the maker was inspired by that crop's abundance in Richland County.

SC82.54.5

Unknown Maker, 1860

Spartanburg County

Donated by Mary Alice Jones

This quilt features fabrics dyed with indigo, one of the oldest dyes used for textiles. Synthetic indigo dye was not available for another 50 years after this quilt was made. The fabric is calico, which is an all-cotton, plain-weave fabric often printed with small designs. Prints like this were popular in the mid-1800s but manufactured well into the 19th century. The use of a natural indigo dye and overall design help us confirm family history that it was made about 1860.

SC2005.27.1

Sarah Ann Wright (1800-1863), c. 1850

Laurens County

Donated by Sandy Henry

Pattern names can be very local and open to interpretation by individual quilt makers. This quilt pattern is often called Rose of Sharon or Whig Rose and is a variation to the pattern next to it. Can you see similarities? It is unlikely the makers used these pattern names. While this pattern was popular in the 1800s, the first use of the term Whig Rose appeared in print in 1912. What name would you give this pattern?

Rocky Mountain Pattern

These quilts feature the Rocky Mountain pattern and use “turkey” red and "cheddar" yellow fabric, common to Upstate quilts of this time. Turkey red gets its name from the country where the English first encountered this color of fabric, but it originated in India. Cheddar yellow first appeared after 1850 in Pennsylvania quilts. The first quilt has a border that might seem unconnected to the rest of the quilt, but this choice is another regional trait. The second quilt is an unfinished quilt top made by Helen Stribling.

SC89.98.1. Eliza Shuler (1835-1914), c. 1860. Orangeburg County. Donated by Bernice Fairy Boone.

SC94.82.4. Helen Sheldon Stribling (1859-1941), c. 1880. Spartanburg County. Donated by Davy-Jo Ridge.

What do you see?

Do you see stylistic echoes between these Pennsylvania Dutch objects pictured below from the 1780s and some of quilts above? Many quilt scholars believe German decorative arts influenced American quilts.

What do you think?

Images courtesy of Wikimedia

Rhyme Not Repeat

Some quilters revel in the rigidity of repeat patterns and the mathematic certainty of squares, triangles, and hexagons. Others break from those patterns from a personal desire to explore the form, while others are simply making do with materials they have on hand. Those choices can be guided by traditions that bind people together over hundreds of years, and across continents and oceans. New crazes can also spur these innovative designs. As globalization connected more people it gave quilters new inspirations. Technological changes, like a seemingly unlimited choice of affordable fabrics, also drove new styles.

Strip Quilting

Strip quilting is taking scraps of cloth and sewing them into strips and then assembling them in multiple patterns. This style has been especially popular among African American quilters. Their enslaved ancestors brought and kept alive West African textile traditions and styles visible in their quilts. Rhythm and improvisation, much like in jazz music, are prized over strict repetition. There is also a preference for bright and high-contrasting colors and bold, large-pattern designs in these quilts.

While these quilts are often made from scrap material and have an improvisational style, do not think they were poorly executed or slapdash. Many of these quilts were expertly constructed by quilters who had an intimate understanding of visual context and the power of color and line.

SC83.135.1. Arelia Truesdale (1902-1981), c. 1940. Kershaw County. Museum Purchase.

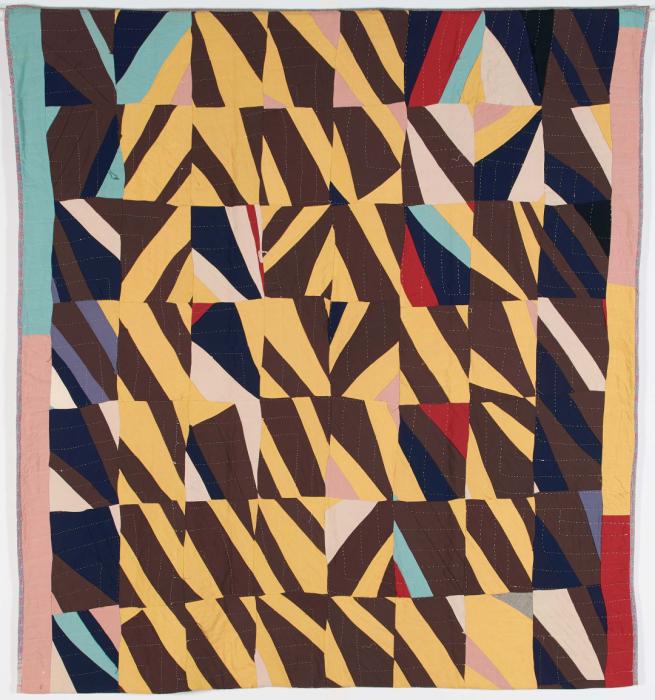

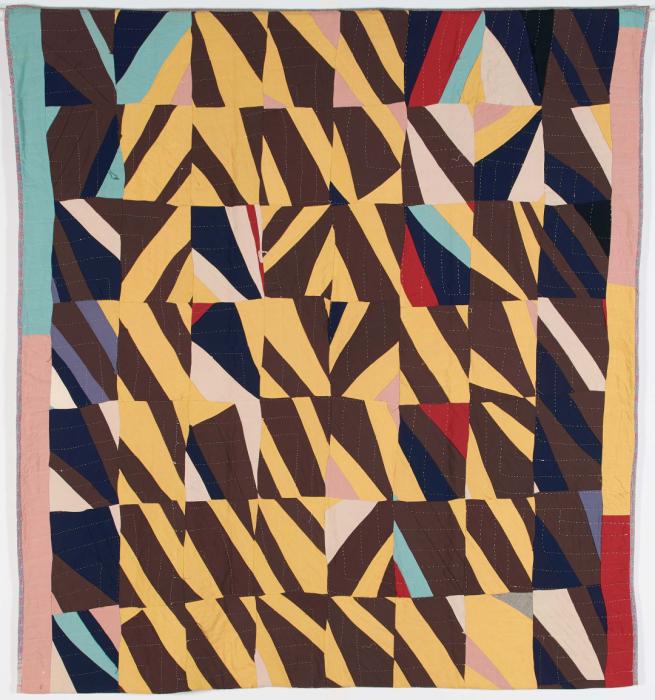

SC83.135.1

Arelia Truesdale (1902-1981), c. 1940

Kershaw County

Museum Purchase

Strip quilting is taking scraps of cloth and sewing them into strips and then assembling them in multiple patterns. This style has been especially popular among African American quilters. While Arelia Truesdale was also known for making Euro-American quilts, in this example she displayed the influence of West African textile traditions passed down through her family. She showcased the asymmetrical arrangements, dynamic contrasts, and prominent stitching popular in West African textiles since the 9th century.

SC85.109.3

Louise Nesbitt (1914-2000), 1984

Georgetown County

Museum Purchase

Louise Nesbitt learned quilting from her grandmother, Bobitt Ohree. In this quilt she created a hand-pieced, one-patch pattern. She often drew on West African textile designs passed down in her family for inspiration. She was presented with a S.C. Folk Heritage Award in 1992 for her work as a master quilter and her community work. She taught quilting and sold quilts to raise money for community projects.

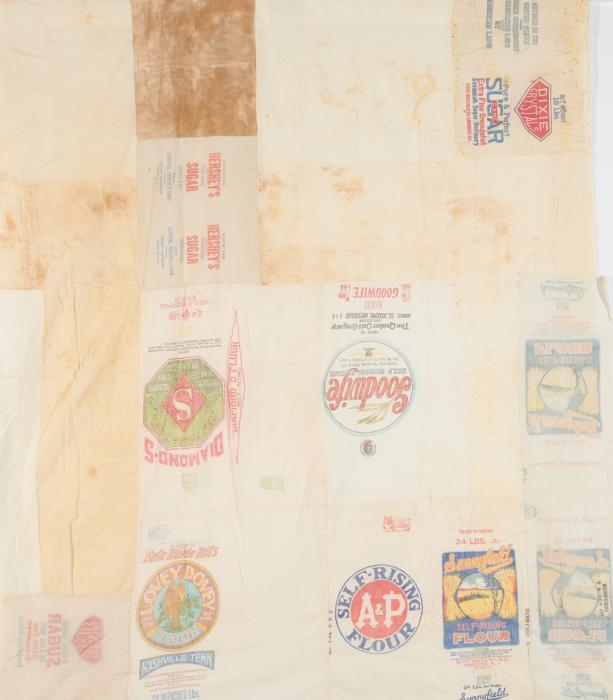

Sack Cloth Quilts

In the late 1800s plain, unbleached cotton sacks took the place of barrels to store dry goods. People repurposed them into things like clothes and quilts. The front quilt features scrap fabric pieces. The back of it is made with feed sacks. The quilt behind it is made entirely of feed sacks. Savvy sack manufacturers caught on and started making their brand names and logos removeable. They also began using printed fabrics. They even included dress and quilt patterns.

SC89.16.3. Unknown Maker, c. 1920. Spartanburg County. Donated by Wayne Wustenberg.

SC89.95.2. Mattie Riddlehoover Smith (1873-1968), c. 1910. Saluda County. Donated by Eugenia J. Smith.

SC85.142.32

Unknown Maker, c.1880

Georgetown County

Donated by Michael B. Prevost

The distinctive style of quilt is called “crazy.” They were a very popular craze from about 1880 to 1900. These quilts showcased imagination and fine needlework. Perhaps you can see the initials "M.L.B.?" This may be the quilter's initials, but that information has been lost. Can you find the ribbon, "Marion's Men of Winyah Bay, July 6, 1880?" What shapes, animals, and other details do you notice?

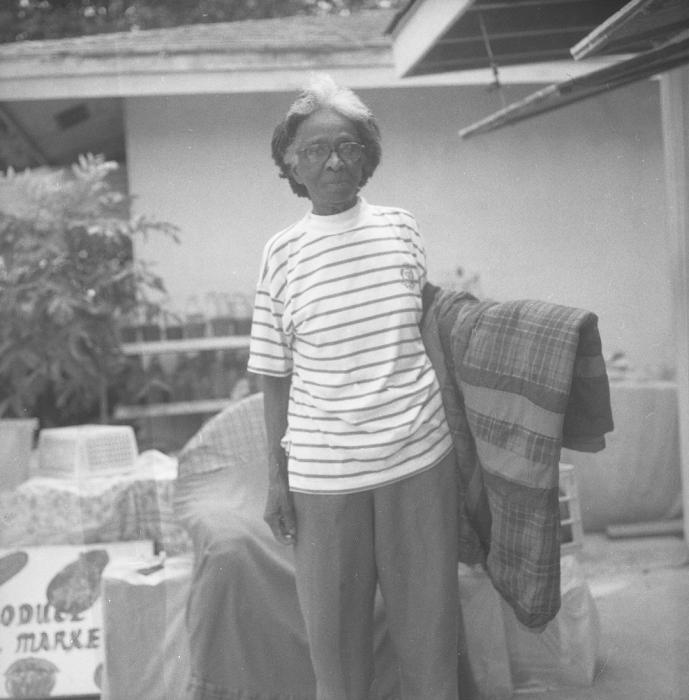

Janie Aiken Grant

Janie Aiken Grant is pictured at her home on Hilton Head Island with this quilt acquired by the museum in 2003. She was as well known for her generosity as her quilting. She often put her skills to use making quilts and clothes for those in need. Like the quilt next to it, this quilt was made from scrap fabric. Skoozi was a popular 1990s clothing line.

Janie Aiken Grant is pictured at her home on Hilton Head Island with this quilt acquired by the museum in 2003.

SC2003.30.1. Janie Aiken Grant (1916-2010), 2003. Beaufort County. Museum Purchase.

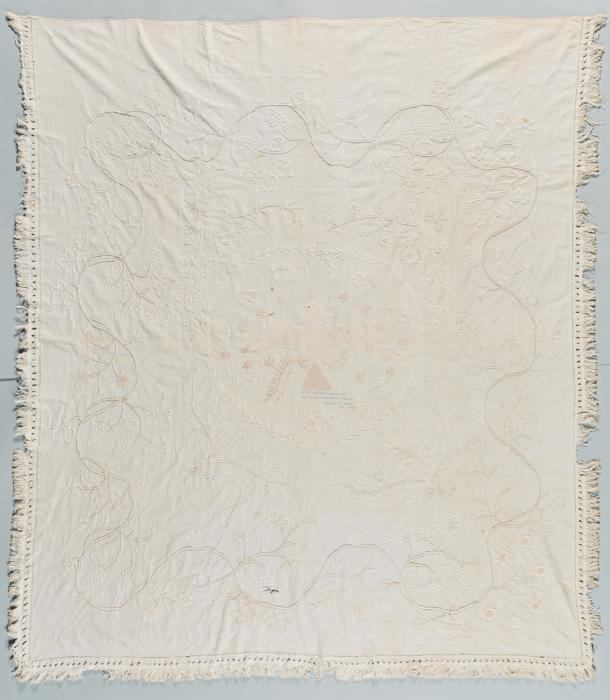

Whitework

Whitework refers to using white yarn and thread on white fabric. It is some of the oldest style of quilting done in America. These bed coverings do not exactly fit the definition of a quilt because the makers often chose to leave out an insulating middle layer. It also allows the maker to execute more delicate quilting.

SC82.106.1. Unknown Maker, c. 1820. Anderson County. Donated by John F. Rainey.

Hand Needlework

The type of hand needlework displayed here is not often seen today. It was the result of decades of experience. For some makers, these quilts demonstrate they had the time and wealth to produce these quilts. However, like other textiles, they could also be purchased ready-made or enslaved needleworkers were a part of their creation.

Design Process

To create these elaborate designs makers could mark out a free-hand design or use a template. They might even purchase a professionally printed pattern, while some women hired painters to mark out designs on the fabric. The marking was done lightly with pencil, chalk, or soap.

Whitework Technique

The bias relief designs were created through a variety of techniques like stuffing loose cotton into areas outlined by quilt stitching, knotting with French and bullion stitches, candlewicking, or threading yarn through quilted channels. They were decorated with white embroidery in different weights of two-ply cotton, wool, or a thick yarn called roving.

SC79.32.1

President Andrew Johnson (1808-1875) and Sarah Word Hance (1807-1883), 1824

Laurens County

Donated by Col. Helen Whiteley

In 1824, Andrew Johnson was a 16-year-old tailor just arrived in Laurens, S.C. He fell in love with a local woman named Sarah Word and proposed. Together they made this quilt. She put her initials on it and left room for his, which she said would have to wait until after they were married. However, her family refused his marriage offer. He soon left town, eventually making his way to Tennessee, entering politics. He became president after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865. Sarah stayed in Laurens, marrying William Hance.

SC82.106.1

Unknown Maker, c. 1820

Anderson County

Donated by John F. Rainey

This quilt features candlewicking, a style of embroidery with soft, bulky yarn and usually using a colonial knot for the stitching. The name of the style comes from needleworkers who began using the thread from candle wicks in their sewing.

SC83.69.1

Teresa C. Acker (1808-1873), 1826

Anderson County

Donated by Teresa F. Bryant

This whitework celebrates the 50th Anniversary of the country's founding. Many women expressed their patriotism and politics in their quilts. For Teresa it may have been more personal since her grandfather, William Acker, fought in the Revolutionary War. In the center she has added: “Blessed may their memory be who fought and died for liberty. Teresa C. Acker, 1812.”

Chintz Applique

Chintz is a printed fabric, often with large-scale, repeat designs. It has a sheen produced by running the fabric through rollers at high temperature and pressure or adding wax, egg whites, or a resin. The process is called calendering and you can still see the effect on some of these quilts.

SC91.101.2. Eliza Adams Simpson (1810-1854), 1827. Laurens County. Donated by John W. Simpson.

Chintz was first imported to the American colonies from India by the English before they manufactured their own. To make the most of this expensive fabric people cut out the decorative elements and appliqued them onto a white fabric.

Block Printing

These oak blocks were used for printing chintz in the early 1800s in England. Block printing is one of the oldest forms of textile printing. Color is applied to the carved designs by roller or pressing the block into a dye pad. As you can imagine, this is a laborious, time-consuming process and a reason why chintz was so expensive.

Courtesy the Science Museum Group Collection.

Popular Prints

You can see similar styles of this fabric to this one in some of the quilts featured in this exhibition. This was a popular design in the early 1800s and was recreated by several English fabric makers. These designs were inspired by well-publicized voyages of exploration and sometimes directly copied from botanical illustrations of the period.

Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum.

SC91.101.2

Eliza Adams Simpson (1810-1854), 1827

Laurens County

Donated by John W. Simpson

Eliza created her Tree of Life design from different block-printed chintz fabrics that date to the 1820s. These were imported from England and appear in other South Carolina quilts.

SC81.147.1

Attributed to the Tillman family, c. 1820

Edgefield County

Donated by Claiborne Good

Broderie Perse is a style of quilt with applique where an image is carefully cut from a piece of fabric that has a white background. It is then appliqued to a white cloth; in this quilt it is a homespun linen. This is done with tiny stitches. The term Broderie Perse is French for "Persian Embroidery" and was done to imitate expensive Indian bedcovers called palampores.

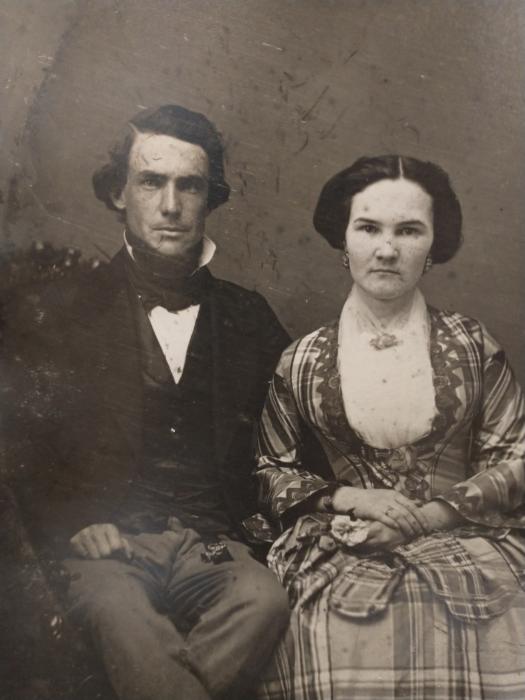

Friendship Quilt

Family history of this Friendship quilt tells us that it was made to celebrate the 1861 wedding of Martha Robertson (1831-1912) to Robert H. Jordan (1830-1873). Friends each made squares and worked together to finish the quilt. We are not sure when Martha and Robert were married but their only child was born in 1856. It is just as likely a group of friends and family came together to enjoy each other’s company and create something beautiful.

SC89.121.1. Unknown makers, c. 1850. York County. Donated by Susan Reeves Deland.

Martha Robertson (1831-1912) to Robert H. Jordan (1830-1873). Courtesy of Susan Reeves Deland.

Patch, Piece, and Repeat

For many, patchwork is synonymous with quilting. While patching fabric has been around as long as textiles to repair rips and tears, using patchwork to refer to a type of quilt was not done until after the American Revolution.

SC82.30.2. Mary Lewis Stevenson (1865-1949), c. 1930. Horry County. Donated by Charlotte Stevenson.

Additionally, using scraps to create an entire quilt was not an option until the mid-1800s. That is when technological advances created a huge variety of inexpensive, highly decorative fabrics.

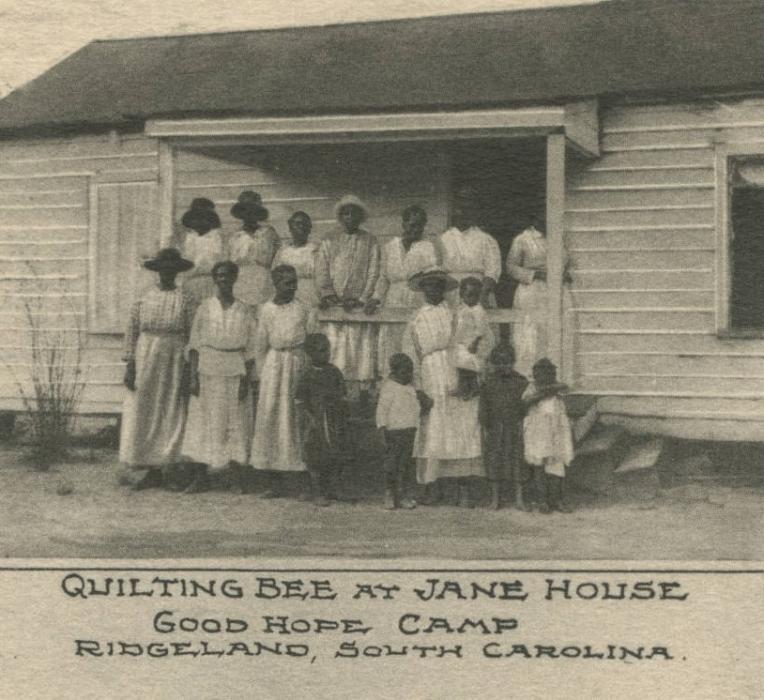

Many Makers

While you may see one name listed as maker of a quilt, it was probably completed by many hands. Often women constructed a top and then invited friends and family over to do the quilting. Quilting bees, as they were called, were important social and community events. These images show South Carolina women at quilting bees in the 1930s and 1940s.

Courtesy the Library of Congress and the University of South Carolina.

Courtesy the Library of Congress and the University of South Carolina.

SC84.77.1. Unknown maker, c. 1840. Possibly Charleston County. Museum purchase.

Patchwork

Patchwork, sometimes called piecework quilting, grew in popularity through the mid and late 1800s. Piecing is seaming together fabric pieces repeatedly until the quilt top is the right size. This was all done by hand until the advent of the sewing machine in the 1850s. Yet some quilters still piece by hand. It is easier for some designs and others may just enjoy sewing by hand.

SC84.77.1. Unknown maker, c. 1840. Possibly Charleston County. Museum purchase.

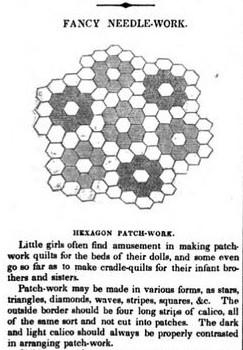

Public Patterns

Below is the first quilt pattern published in America. It appeared in Godey’s Lady’s Book magazine in January 1835. Twenty-five years later, the magazine noted that patchwork “required no additional light for its execution, the work which produces it being slight and easy. The one care which it exacts is a mathematical precision in the foundation shapes of which it is composed, and a knowledge of color.”

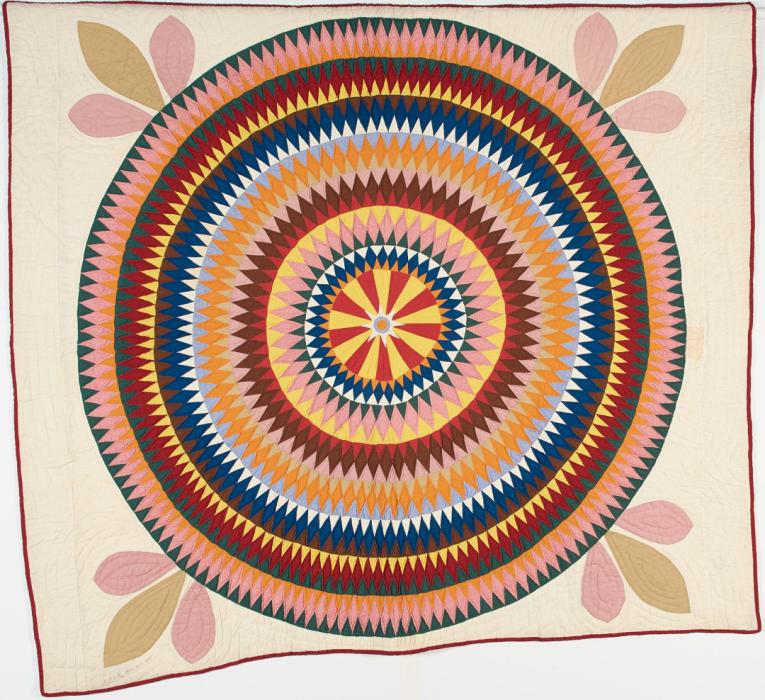

SC79.34.3

Lucy Tucker Catlett (1834-1927), c.1880

Anderson County

Museum Purchase

This quilt was made by Lucy Tucker Catlett for her daughter Mary Alice. It was probably given to Lucy when she married David Vance of Ashville, NC in 1879 at the age of 16. It is marked, " MACV from her mother.” These fabric pieces were all carefully collected and planned out and were not sewing scraps. The maker hand-pieced them into this difficult-to-execute circle shape. The “petals” in the corner have fugitive dye and were most likely green when new.

SC2000.71.1

Annis Amelia Drakeford, c. 1850

Kershaw County

Donated in Memory of Margaret McDowell Mullen and Amelia McDowell Shealy

This quilt is a wonderful smorgasbord of mid-19th century fabrics. Unfortunately, many of the vibrant colors have faded. When the dye fades it is called "fugitive." We can guess at the original color by looking at the seams where a bit of true color may remain. For dark colors, iron was often used in the mordant, which makes the dye hold to the fabric. That caused corrosion and deterioration.

SC82.30.2

Mary Lewis Stevenson (1865-1949), c. 1930

Horry County

Donated by Charlotte Stevenson

By the 1920s this hexagon pattern was known as Grandmother’s Flower Garden and made in a different way than its earlier hexagon cousins to your left. This style was made with larger hexagons and sewn together with a running stitch. This was easier to construct, but still quite an accomplishment.

Mosaic Patterns

This mosaic or honeycomb pattern first appeared in England before it arrived in Charleston in the early 1800s. It remained popular there long after it passed out of fashion elsewhere. This pattern was created using English piece work. To do this the maker wrapped fabric around paper templates and stitched it to the paper. Those are then whip stitched together. Once the top is complete, they removed the paper. Many women never finished, leaving the paper attached.

SC84.77.1. Unknown maker, c. 1840. Possibly Charleston County. Museum purchase.

Spot the Mistake

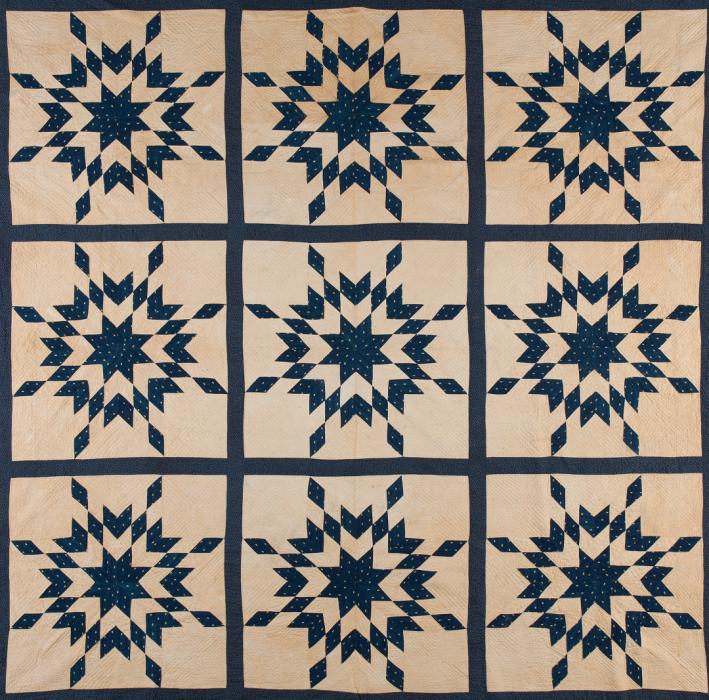

SC85.109.1

Carrie G. Coachman (1943-1999), 1985

Georgetown County

Museum Purchase

There are many quilt myths. One is that quilters purposely add mistakes to quilts rather than offend God by creating a perfect quilt. The truth is that quilting is very difficult, and mistakes are a part of the process. Carrie Coachman, who also made the red, star quilt at the front of this exhibition was a master, award-winning quilter. The "mistake" she put in this quilt seems an intentional, playful interruption of the friend-ship pattern. Can you spot it?

We hope you enjoyed this online exhibition experience!

If you have questions or comments, please send an email.